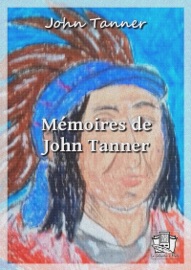

The story of John Tanner is the tragic and age-old story of a man who had no country, no people, no one who understood him, no place to lay his head.

His Narrative, which is the story of his thirty years’ captivity among the Ojibways, was written a few years after he settled once more among the civilized whites. The material was written down and edited by Doctor Edwin James, and James’s foreword gives a hint of the almost insurmountable difficulties that surrounded Tanner’s attempt to establish himself among the whites. However, the real story of John Tanner’s long and tragic life unraveled after the book was printed in 1830, for Tanner spent sixteen more years trying to find a place for himself in white society.

Here was a man who had lived as a white boy only nine years, had then been captured and had spent thirty years among the Indians, had married an Indian woman and produced half-breed children, had in every way—physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually—lived as an Indian for so long that he forgot his own name and could no longer speak the English language, but still was impelled by some ancient hunger to try to find his own people, to be a member of the society that had borne him.

He found it—as so many other Indian captives have found it—impossible. Though he rejected his Indian foster people and settled among the whites, educated his halfbreed children in white schools, still he was too much Indian to change environment. His Indian characteristics made him “different.” He was distrusted by the whites. He was not prepared or equipped to make a living according to the white standard. Confused and bewildered, his white heritage constantly fighting with his acquired Indian environmental factors, in his later years he was lonely and “bitter.” He is said to have threatened violence against those who opposed him, but to his credit it must be said that no major act of violence has ever been proved against him; the charges have been founded entirely on supposition, and it is obvious that a factor in those charges was his “difference.”

What follows here is largely the story of Tanner’s life after the publication of the Narrative, during the years of struggle when, not understanding and not understood, he tried desperately to be a “white” once more.

Henry R. Schoolcraft, who firmly believed Tanner had killed his brother, said: “ ... now a grey-headed, hard-featured old man, at war with everyone. Suspicious, revengeful, bad-tempered.”

Elizabeth T. Baird said he was cruel and no religion could be discussed before him.

Mrs. Angie Bingham Gilbert, who had known him as an old man when she was a young child, said he had a strange and terrible personality, a violent and uncontrolled temper, but was very religious and almost noble-looking. It rather looks as if Mrs. Gilbert, having spoken her mind, wanted to soften her remembrance of him.

On the opposite hand, William H. Keating, journalist for Major Long, said he never drank or smoked, was honorable, was attached to his children, and had great affection for his Indian foster mother and her family. The latter two items are quite apparent even in his matter-of-fact telling of the Narrative.

The truth probably lies in a combination of these points of view. Keating knew Tanner in 1823, before Tanner had a chance to become disillusioned as to his place in society. Even before Tanner left the Indians he learned to drink, but rather conservatively, it would seem on the whole. The other commentators knew him later, after he had fought his personal battle with civilization and had lost; when he had found at last that he could not live in an Indian hut, under Indian conditions of sanitation, follow Indian customs in treatment of his family, and still be accepted as a white. Here then, it might seem, was a man who, battling with his own inner turmoil of ideas and evaluations, unaccountably found himself in desperate conflict with the mores of his native race. He fought back, it would seem, with considerable restraint, considering his background, and in the end, lonely, friendless, his oldest daughter separated from him by legislative edict, the people of his adopted town holding him in alternate contempt and awe, even his friends beginning to fear violence from him, he disappeared under a cloud.