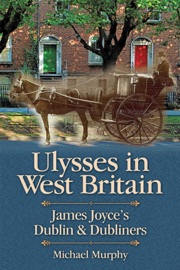

The term “West Britain” for Ireland was worn proudly by those loyal to the English Crown, but for patriotic Irishmen it was a slight. In Ulysses and Dubliners, Joyce presents the men of Dublin as reluctant but impotent citizens of West Britain rather than of Ireland.

Ulysses is widely commemorated now on Bloomsday as a celebration of Joyce’s native city. Ulysses in West Britain insists that Ulysses is not a salute to Joyce’s Dublin or its citizens, nor a cry de profundis for its release from colonial oppression. Joyce’s satire on Dublin and Dubliners is directed not at the oppressor but at his own fellow citizens, those he called sarcastically the “gratefully oppressed.”

When life in the Dublin of Ulysses isn’t shabbily unheroic, it is an undivine comedy, laced with mordant Swiftian humor. Even the lives and deaths of Irish patriots are made objects of derision rather than respect. Joyce was wrong that there are no heroes and there is no heroism in Dublin or in ancient Greece. He was simply unable to see it. Though Joyce’s work is fashionably presented as “post-colonial” in much recent criticism, post-colonial in any positive sense it is not.

In Ulysses the heroic tale of The Odyssey is inverted to an anti-epic. Odysseus subverted an enemy city with a group of valiant men and a horse made of wood; Joyce does it to his hometown alone and unheroically with a devilishly ingenious explosive made from paper and print. Among other things, this book explores some ways in which he manages it.